The Taxing Taxonomy of Taxes (IRA Edition)

People often overlook the importance of taxes in their investment planning. They also don’t often maximize the use of IRAs and 401ks in their tax planning. It is not just about how much money you invest in your IRAs; it is also about which types of assets go in which types of accounts. Do you put the same mix of investments in all your accounts, or do you put your bonds in one type of account and stocks in another? For that matter, should you have some of your savings in a taxable account if you already have a lot of your money tied up in IRAs? These are important questions, and the answers can be surprising and can change with your age. If you have not discussed these kinds of questions with an advisor before, you should read on.

Ben Franklin famously quipped that there are only two things certain in life, and one of them is taxes (and the other is a taxable event). Yet given that certainty, it is rather amazing how secondary the consideration of taxes is to investment planning across much of the industry. There are reasons for that, most notably because the tax code seems to have been written by a gaggle of Mongolian cat herders using Google Translate. [1]

Last year was a very rough year for almost all investment asset classes. Prices got clobbered as the Fed aggressively hiked interest rates to combat inflation. The S&P 500 stock index was down about 20% for 2022 while the NASDAQ was down a staggering 30%. Even the normal safe haven of bonds did not provide much of a cushion for this pull back, as the Bloomberg Aggregate US Bond Index was down more than 13% for the year. There was almost nowhere to hide apart from cash, and more than a few mattresses got extra padding.

In a year that was filled with disappointing losses, the silver lining was that sometimes you could reduce your taxes if you planned it well. As the holiday season approaches every December, financial advisors root through their sack of assets looking for leftover presents – i.e., capital losses. That led us to think maybe this quarter we should do a refresher course on investment taxes and tax planning. Yet, as we set out to write this note, we began to realize what a massive topic it is to cover all of the quirks of investment taxes in one go. Instead, we are going to break it into multiple white papers, starting this quarter with the tax advantages and disadvantages of using IRAs and other tax-deferred and tax-free investment accounts. If there is only one takeaway from this note, let it be that taxes are complicated and specific to a person, but that doesn’t mean they have to be scary or ignored. A little tax planning with your investments can go a long way toward improving your after-tax investment returns and net worth. So, let’s dig into it.

Why Taxes Are Half the Ball Game

There is an unaddressed issue in the investment industry with how returns are measured, because everything is assessed before tax. This means a fund manager can trade in and out of stocks and bonds, incurring any number of taxable events but still come out showing the total return as if there were no tax costs to the investor. In some cases, there aren’t, but more often there are. If you have an actively managed fund in an IRA, for instance, generating all that taxable income does not have any actual effect on your taxes, at least in the near term. Traditional IRAs are a vehicle for deferring tax, and so whatever gets generated in them has no tax effect in the immediate term.

However, when the money is ultimately paid out to the investor – usually during retirement – all withdrawals are treated as regular taxable income. So, there is a tradeoff because the tax rate that you ultimately pay may be a lot higher than the tax rate for dividends and capital gains.

Rather than paying a 15% federal tax on dividends and capital gains, you could be paying as high as 37% for federal tax alone (depending on your tax bracket, which varies with your income level and can be affected by how much you withdraw and at what age).

For those who are not very familiar with how investment taxes work, here is a quick, non-comprehensive primer. [2] Feel free to skip past this summary if you are already savvy with investment taxes. We promise not to tell anyone what a nerd you are.

A Quick Summary of Investment Taxes

- Capital Gains. Any investments held in a taxable account would be subject to capital gains

tax when the investment is sold, if the value has increased. There are lots of complexities

within the tax code about certain special circumstances, but in most cases it is pretty simple.

If you bought a stock at $100 and then sell it for $120, your taxable capital gains would be that

$20 of increased value, or profit. Importantly, though, taxes would only be due if and when the

asset is sold during a given tax year. In other words, all those mega-rich billionaires who are

avoiding paying much in taxes are often taking advantage of the fact that they don’t have to

sell their huge holdings unless they want to. (Indeed, they can build giant phallic-rockets just

by borrowing money against their vast wealth, thus never selling anything). The tax rates on

actual realized capital gains (i.e., actually sold assets) generally take one of two forms:

- Long-term Gains. Investments that are held for 12 months or more before they are sold would be treated as long-term capital gains. The tax rate for long-term gains is much more favorable – only 15% for federal taxes in most cases, though it can be 20% for very high earners.

- Short-term Gains. For investments that are held for less than a 365-day period, any gains are considered short-term gains and are taxed at your regular income tax rate. Usually, that rate is higher than the 15% long-term rate, which is why investors are incentivized to hold investments for at least a year.

- Offsetting Gains with Losses. A quirk of the tax system is that your capital gains can be partly or fully offset with capital losses. In other words, if you sell some securities for a profit and sell some others at a loss, you can generally offset one against the other and only pay tax on any net amount of gain. The rules are complicated between short-term and long-term gains, but the principle pretty much applies to all gains irrespective of holding period.

- Dividends. When companies pay ordinary dividends to shareholders (cash payout), those investors benefit from a dividend tax rate that is also 15% on the cash paid for most taxpayers, provided that the dividends are classified as ‘qualified dividends’. In practice, most companies traded on US stock markets are in the qualified dividend category if they pay dividends.

- Offsetting Gains with Losses. A quirk of the tax system is that your capital gains can be partly or fully offset with capital losses. In other words, if you sell some securities for a profit and sell some others at a loss, you can generally offset one against the other and only pay tax on any net amount of gain. The rules are complicated between short-term and long-term gains, but the principle pretty much applies to all gains irrespective of holding period.

- Interest Income. Bond interest, and for that matter, any interest income, is treated just as regular income and taxed at your income tax rate. However, what qualifies as interest income on bonds may sometimes surprise you, because it is not as simple as just the interest paid to you by the company/issuer. Instead, if you buy a bond ‘at a discount’ to its face value, the tax authorities require you to amortize the implied interest rate whether received in cash or not. The complexity of these calculations go beyond what we can include here, but it is important that you are aware of this quirk if you are a holder of bonds.

- Other Income. Other forms of income, such as premium income paid for options, are typically treated as regular income. However, in some cases this investment income can be offset with investment losses in a way that normal interest income or dividends cannot. Real estate investment trusts have additional complicated rules.

IRAs and 401ks – The Procrastinator’s Way of Paying Tax

All of this brings us to this quarter’s topic: the uses of tax-deferred vehicles like traditional IRAs and 401ks and tax-free vehicles like Roth IRAs. Since a very large number of investors already have one or the other of these tax-deferred accounts, most people think they have a pretty solid sense of the advantages and disadvantages. Yet, it is not a binary decision. If you have one of these types of accounts, that means you are already making investment allocation decisions for them – whether actively or not. Interestingly, almost nothing gets written about the complicated question of what kind of assets go in which kind of account because it is, well, complicated. You know the kind of word problem you used to get on exams that seemed to make no sense: “if Bob leaves the office at 12.30 p.m. at 40 mph and his wife Jane leaves her home driving an SUV but hasn’t yet set up a Roth IRA, where should each of them put their real estate investment trust allocations?”

Traditional IRAs and 401ks do not avoid tax – they just push the tax effect back to a later date when you are in retirement. Roth IRAs and 529 Plans (for education) grow completely tax-free, but you don’t get to shield any of your federal income at the time of investment or use future capital losses to offset gains (an often-overlooked benefit of having some investments in taxable accounts). For the purposes of these discussions, we refer to traditional IRAs/401ks and their cousins as tax-deferred accounts, whereas we use the parlance ‘tax-free’ for Roth IRAs and 529s.

The reason a traditional IRA is considered tax-deferred is because you ultimately have to pay tax on every dollar you distribute from them (i.e., you don’t avoid tax, just delay it). This also can mean that the tax rate you will pay in the future could be higher than you are paying on income now. It also is likely to be higher than the long-term capital gains tax rate. Complicating this equation is that at age 72 (possibly 73), an investor has to begin to take Required Minimum Distributions whether they need the money or not, and these increase as you age with little regard for what it does to your tax bracket.

As a result of these issues, there are very lively debates about what portion of your savings should be invested in these tax-deferred accounts versus kept in taxable brokerage accounts.

We are going to skip past this debate as gracefully as we can for two key reasons: (1) there are limits to how much you can invest in tax-deferred accounts per year, making it something of a moot point for high-income savers; (2) many people already have well-funded, tax-deferred accounts; and (3) the costs and benefits are going to be very dependent on a person’s specific tax circumstances and projected future tax rates. So much for dodging that question.

Let’s instead look at what you can do with your investments once you already have both investments in taxable accounts and IRAs/401ks. How can Bob and Jane (or you) use these various accounts to maximize one’s after-tax wealth?

Example 1: Is tax-deferred always the best place for stocks?

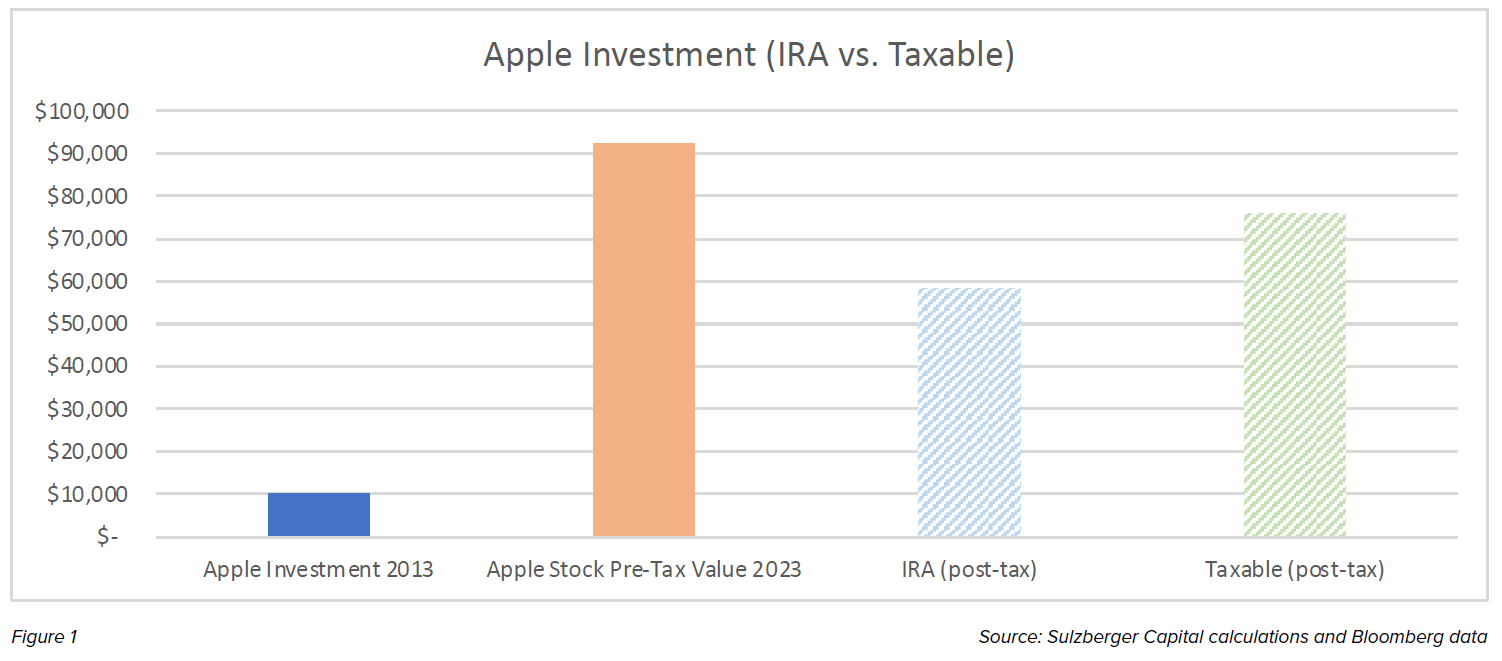

Let’s start with a fairly simple example. Suppose you want to buy stock in Apple (AAPL) to hold for 10 years to use toward a downpayment on a house in your first year of retirement. Let’s also say that you have the ability to buy Apple stock in either a traditional IRA or your taxable brokerage account. If you otherwise are saving it for retirement, wouldn’t you just buy it in your IRA, which after all, is called an Individual Retirement Account? Well, that’s not necessarily a slam dunk decision. If you truly are going to hold it for 10 years and can resist the temptation to swap it out for other stocks, here’s what $10,000 would have looked like post-tax over the last 10 years. This assumes that at the end of the period you sell AAPL when you start retirement.

Apple climbed more than 800% in the last 10 years, so a $10,000 investment in 2013 would now be worth $92,325 today. That’s a pretty good result whether it is in your IRA or your taxable account. Let’s say, however, that your marginal tax rate in your first year of retirement is 32% and you have a further state tax rate of 5%. In this example, at the end of ten years, your Apple shares would be worth a little over $58,000 after taxes at the time of the IRA distribution, whereas it would be worth almost $76,000 if you just paid capital gains tax for the sale in your taxable account.

In total, you would have a staggering 30% more after-tax wealth if you had made the same investment in a taxable account rather than an IRA. Note that we are ignoring for this discussion the original taxdeferral benefit you would have received on the IRA contribution, focusing only on what is done with the allocations once you have both types of accounts.

A critical reason for getting this after-tax wealth effect is that you can also defer taxes in a taxable account just by not selling your stocks or by offsetting gains against losses. It is kind of like a taxdeferral, but with a lower ultimate tax rate than you may have for your IRA. Now a smart-aleck wealth manager will point out that the preceding analysis makes a big assumption that you are not rebalancing your stocks in a multi-stock portfolio, because maybe the Apple shares became too large relative to your other positions. That’s a fair argument, but a good manager should be able to work around these constraints to minimize net capital gains taxes. Without getting bogged down in the specifics, there are also ways to rebalance portfolios that avoid this problem of frequent sales.

Example 2: Where do I put my bonds?

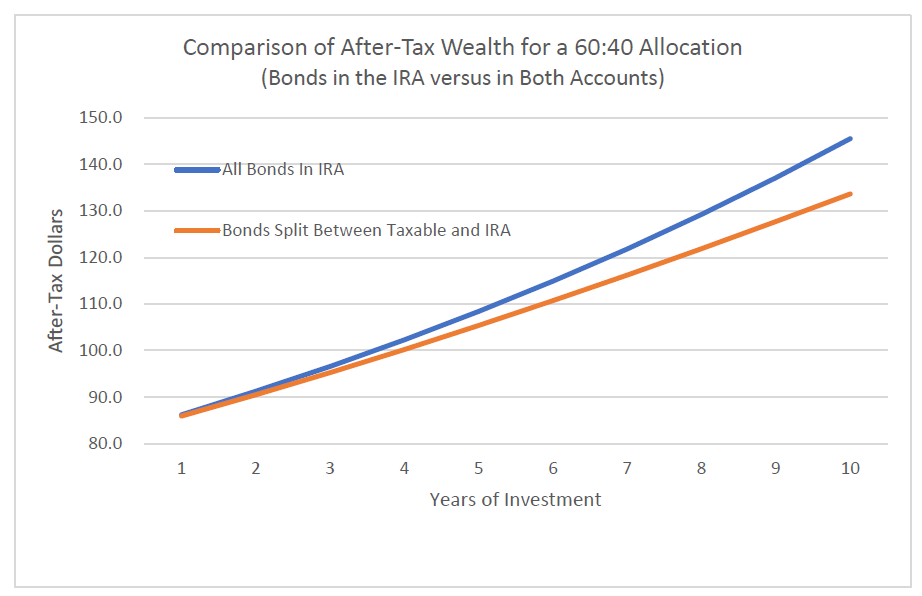

In Example 2, let’s take a seemingly simple case of an investor who already has $100,000 invested – half in a traditional IRA and half in a taxable brokerage account. Now let’s also assume that the investor wants to pursue a classic strategy of maintaining 60% of their investments in stocks and 40% in bonds, adjusting annually to bring the 60:40 balance back into alignment. In this question, we want to ask “in which accounts should the bonds be invested?” Do you put all of them in your IRA so that you don’t pay interim taxes on interest payments to you, or do you hold the 60:40 allocation in each of your taxable and tax-deferred accounts, spreading the bonds between them?

This may seem like a simple question, but it most definitely is not. Because the bonds are paying interest on an ongoing basis, there could be a benefit to having them temporarily shielded from tax in the IRA without changing your overall investment risk allocation. However, some managers will argue – sometimes persuasively – that stocks will grow at a much faster rate, so shielding that larger growth in the IRA until retirement will be more beneficial and avoid more taxes. So, which is right? Well with a couple caveats [3] specific to an investor, we set out to model after-tax wealth for each of these allocations by account using exactly the same 60:40 strategy. Here’s what it looks like for a person whose marginal income tax rate is 32% for federal and 5% for their state:

In this specific set of circumstances, putting all the bonds in your IRA ends up being a better plan. Starting out with $100,000 before tax and using exactly the same risk allocation in both cases, the allocation with all the bonds in the IRA ends up with close to $12,000 more after taxes at the end of 10 years. That’s about 9% wealthier than splitting between accounts. Why is that? There are actually two key reasons. Firstly, as we mentioned, the bonds pay interest on a current basis, so it is going to incur a tax hit each year. You are effectively getting a lower interest rate on your bonds. Secondly, any rebalancing to bring you back to the 60:40 ratio in the taxable account could result in capital gains taxes. If the financial managers are doing their job well, then odds are good that you are better off putting all or most of the bonds into your IRA over the long haul.

Optimizing the Use of Your IRAs

The examples above give a sense of just how complicated this tax optimization can quickly get. When you are working with a wealth manager, this kind of optimization is rarely going to be measured, and this makes it very hard to know if you are doing the best things with your money from a tax perspective. Just to reiterate, the performance measurement standards for returns in the financial services industry are all done pre-tax. The regulatory standards say that managers are obligated to make tax decisions appropriate for individual investors’ tax situations, but without measuring post-tax effects, this becomes something of an unprovable goal. [4]

With the caveat that tax planning will be unique to each investor’s risk and circumstances, there are a number of other rules of thumb for IRAs beyond just putting your bonds in tax-deferred accounts:

- Maximize Matching Funds. If your employer provides matching funds for 401k or 403b contributions, then you almost certainly should invest at least enough from your salary into these accounts to get the full matching benefit. It would be a rare set of circumstances where that free money should be turned down.

- Have a Mix of Accounts. To the extent that you qualify, you are almost certainly better off having different types of accounts to help optimize your ultimate tax burden. Tax-deferred accounts, tax-free accounts (Roth IRA, 529s), and taxable accounts all have a place in your wealth mix and can help you to structure for the best tax treatment for your investments over the long term. Many people make the mistake of maximizing their 401k contributions, even beyond matching funds; but, they don’t maintain any investments that are available in a taxable account for possible need before retirement. You should have a nest egg, not just a retirement egg (where you have to wait 20 or 30 years for it to hatch). Think of holding different types of accounts as a form of diversification, since you can’t know what the future holds.

- Roll Over any Old 401ks into Rollover IRAs. Many investors don’t feel the need to move money that they have invested in a previous employer’s 401k plan to transfer it into a Rollover IRA. You can almost always get more investment choices – and therefore more tax planning flexibility – if you have your money in a Rollover IRA compared to a 401k or 403b. They are all tax-deferred accounts that work essentially the same way, but 401k plans will only have a limited set of mutual funds in which to invest to meet broad categories of risk, capital appreciation, and/or income. They can be too limiting for tax planning later. Such a conversion of an account would not need to be rolled over to a managed account to provide this potential extra flexibility.

- Choose Tax-Efficient Investments in Your Taxable Account. Mutual Funds have their place, but they are not very tax efficient. If you have money invested in a taxable investment account, consider whether you can hold ETFs or individual stocks and bonds rather than mutual funds. ETFs can provide the same exact holdings as a mutual fund but do it more tax-efficiently. Individual stocks can postpone taxes as well. On the surface, ETFs and mutual funds look pretty similar. Yet mutual funds are required to pass through any capital gains or losses on an annual basis for any sales of securities they had to make, particularly if a lot of people cashed out at the same time. You don’t want to be slammed with unexpected taxes, and ETFs generally allow you to defer most capital gains taxes until you yourself decide to sell it.

- Consider Diversifying Your Employee Shares/Options. This is a very specific problem, but some investors also get some portion of their compensation in their employer’s stock. For every Microsoft or Paypal manager who ended up a multi-millionaire just by holding their company’s stock plan for ten years, there are another hundred people who saw a lot of paper wealth evaporate overnight. There is nothing wrong with having a large portion of your wealth tied up in employer stock if you believe in that future, but it really should be integrated with your broader wealth planning. Sometimes a few stock sales along the way can be a prudent outcome. At the minimum, you can manage your non-employer portfolio to help diversify against the risk of too many eggs in one basket and try to offset any tax effects.

- Consider Putting Actively Managed Assets in an IRA. If for a particular reason you want to hold some funds with actively managed strategies (as distinct from a passive index fund), you could consider making that investment through your IRA. Actively managed funds, particularly mutual funds, can generate a lot of interim sales that could be taxable. This is one of the key reasons why active management is often a poor choice over index ETFs, but there are certain strategies that don’t have a simple index alternative. Allocating those positions in your IRA could defer any taxes and eliminate the problem of interim taxes – much as we suggested with bonds.

- Coordinate Across Managers. You can’t really optimize your taxes if you don’t know the tax treatment of your different holdings. The right hand may be incurring taxes that the left hand could avoid. If you have assets with a lot of different managers or retirement plans, someone needs to coordinate a plan for all your wealth management: someone has to be your team’s quarterback. This goes well beyond just tax effects, but taxes are a very important component of this coordination.

Advanced Stuff with Tax-Deferred and Tax-Free Accounts

In 2021, a lot of news coverage and Congressional hubbub ensued over the disclosure that billionaire investor Peter Thiel, a Paypal founder, had accumulated $20 million or more in a Roth IRA completely tax-free. That’s a $h#t-ton of tax-free money considering that the annual contribution limits are $6,000 - $7,000. Leaving aside how Peter Thiel managed to qualify in the first place for a Roth IRA, the episode illustrated the remarkable potential for tax planning in IRAs when used creatively. Our example above underscores that something as staid as where you put your bonds can make a notable difference in your after-tax wealth.

You don’t need to be a billionaire to do advanced tax-planning stuff. Here are a few examples to whet your appetite (but don’t try these at home without expertise):

- Do the Peter Thiel Roth-IRA Two-Step. Taking a page from his playbook, an investor who has a portfolio-appropriate allocation of higher risk assets could make those investments in their Roth IRA. Thiel magnified the effective transfer of wealth into tax-free form by making investments in early-stage venture capital and also taking positions with higher risk stock options. You don’t have to be a risk-happy billionaire, though, to have some portion of your portfolio in high growth companies and even pre-revenue companies that are essentially venture capital investments. A prudent retail investor probably should limit this to no more than 5% of their portfolio, but if you otherwise have an allocation, the Roth might be a good place to park it. No one is promising you will end up with $20 million there, but we can all dream.

- Sell Yourself a Call Option. This is just shy of being too clever by half, but you can use call options on stocks (the right to buy at a given price) essentially to transfer future growth of a stock you hold into a tax-free or lower tax form. An example of this would be to ‘sell yourself a call option’ on a stock you hold in your IRA, buying the very same position in your taxable account that you sold in your IRA. Without significant changes to your risk profile overall, any excess growth of the stock accrues to the targeted account. This is something that might be done by investors who believe that too large a percentage of their wealth is in IRAs/401ks or who are in early retirement and are concerned about the IRA tax effects later from required minimum distributions. If the stock increases past the callable price (strike), you can then exercise the call option and defer any gains in your taxable account indefinitely. If the stock goes down, you get the benefit of capital losses that you otherwise would not have had because it was in your traditional IRA. This can be beneficial for certain investors with significant accumulated capital gains.

- Take Advantage of Opportunities When Your Tax Rates are Low. There are years in most people’s lives when they take an extended time off of work, start a new job, have a child, start a business or otherwise find themselves making a lot less salaried income during a calendar year. You may be able to take advantage of your lower tax rates to make changes to your types of accounts. For instance, you could convert some of your traditional IRAs into a fully tax-free Roth IRA. This requires you to pay tax on the converted amount as if it were normal income, but if you are in a lower tax bracket, this may actually be a savvy financial move. If you expect to have a lower income in a year, make sure to ask your financial advisor about possibilities.

- In Retirement, Plan Where You Take Income for Tax Purposes and When. It is really common for retirees to set up a recurring payment from their IRAs so that they have a steady, predictable amount of income. That may be the least complicated, but it is not always the most tax efficient. For instance, sometimes taking a little more from your Roth IRA over your Traditional IRA can keep you in a lower tax bracket, effectively reducing the tax hit on each incremental dollar you distribute. Similarly, you can use offsetting capital losses and gains in a taxable account to do essentially the same thing. Managing between different types of accounts gives you this flexibility.

- Adjust Where You Hold Maturities for Bonds/Bond Funds Between Accounts. Not everyone has the luxury of putting all their bonds in an IRA to defer taxes on the interest income (as we did in Example 2 above). Sometimes you need some backup capital in case you buy a house, or you may need some ongoing income. In the environment of early 2023, short maturity bonds are actually yielding more (paying total income that is greater than long-term maturities). It could make sense to put higher yielding bonds in the tax-deferred vehicle, all other things equal. Again, it will depend on the situation, but it is worth asking.

9 The broader point here is that smart tax planning isn’t just about knowing tax rules – it is all about how strategic you are in using them. IRAs and other tax-deferred and tax-free accounts are a critical tool in this effort. Despite its importance, your financial managers are not really compensated or assessed based on this planning capacity. We are also probably a decade away from the point where AI can plan your allocations with tax optimization as one of the criteria. In the interim, it is all going to start with you and how you position yourself for after-tax wealth as the goal. You and your advisor need to be aligned in these goals, and it likely means sharing a lot of your personal tax information. Have that conversation with your advisor, and don’t forget to loop in your tax accountant. Who could turn down a chance to chat with a tax accountant?

1 No disrespect is meant to any Mongolians or people engaged in the profession of cat herding.

2 This summary is necessarily abbreviated and should not serve as a substitute for consulting with a tax advisor. A more complete explanation of investment taxes can be found in the IRS publication 550 (Publication 550 (2021), Investment Income and Expenses | Internal Revenue Service (irs.gov)). Sulzberger Capital Advisors is not an accounting firm and does not staff CPAs.

3 This analysis depends critically on the tax rate of the individual and the assumptions of rates of returns for each type of asset. It can vary significantly from investor to investor.

4 Managers would also typically charge fees, so this can affect the net returns while also being tax deductible in some cases.

- Sulzberger Capital Advisors, Inc. is registered as an investment advisor with the state of Florida. The firm only transacts business in states where it is properly registered, or is excluded or exempted from registration requirements. Registration as an investment advisor does not constitute an endorsement of the firm by securities regulators nor does it indicate that the advisor has attained a particular level of skill or ability.

- This white paper should not be construed as personalized investment advice or as an offer to buy or sell the securities mentioned herein. A professional advisor should be consulted before implementing any of the strategies presented. All investments and investment strategies have the potential for profit or loss.

- Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that any specific investment or strategy will be suitable or profitable for a client’s portfolio. Asset allocation and diversification do not ensure or guarantee better performance and cannot eliminate the risk of investment losses.

- Investments in bonds are subject to liquidity risk, market risk, interest rate risk, credit risk, inflation risk, purchasing power risk, and taxation risk.

- Any illustrative models presented in this document are based on a number of assumptions and are presented only for the limited purpose of providing a sample illustration. Any sample illustration is inherently subject to significant business, economic and competitive uncertainties and contingencies, many of which are beyond the control of Sulzberger Capital. Any sample illustration is not reflective of any actual investment purchased, sold, or recommended for investment by Sulzberger Capital and are not intended to represent the performance of any investment made in the past or to be made in the future by any portfolio managed or advised by Sulzberger Capital Actual returns may have no correlation with the sample illustration presented herein, and the sample illustration is not necessarily indicative of an investment that Sulzberger Capital will make. It should not be assumed that Sulzberger Capital’s investment recommendations in the future will accomplish its goals or will equal the illustration provided herein. A more detailed description of the assumptions utilized in any of the simulations, models, and/or scenario analyses is available upon request.

- Historical performance results for investment indexes and/or categories, generally do not reflect the deduction of transaction and/or custodial charges or the deduction of an investment-management fee, the incurrence of which would have the effect of decreasing historical performance results. Returns do not represent the performance of Sulzberger Capital Advisors, Inc. or any of its advisory clients. There are no assurances that a client’s portfolio will match or outperform any particular benchmark.

- Content should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors on the date of publication and are subject to change.

- Projected growth may be better or worse than the projections. Projections are based on assumptions that may not come to pass and are used for illustrative purposes only. Projected growth does not reflect the impact that taxes, investment expenses, and advisory fees will have on the results. Projections are derived from sources deemed to be reliable. No warranty or guarantee is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Social Security rules and regulations and tax laws are subject to change at any time.

- All information is based on sources deemed to be reliable, but no warranty or guarantee is made as to its accuracy or completeness. Discussions should not be construed as recommendations by Sulzberger Capital to buy or sell any specific security.